Plato vs. Aristotle: Comparing Two Philosophical Giants

Detail from Raphael's "School of Athens" (1509-1511) depicting Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), symbolically representing their different philosophical approaches: Plato points upward to the realm of Forms while Aristotle gestures toward the earth, emphasizing empirical observation.

Introduction: Teacher and Student, Two Philosophical Paths

Plato (428/427-348/347 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCE) stand as the two most influential philosophers of ancient Greece and perhaps of all Western philosophy. Their relationship—Aristotle was Plato's student for nearly twenty years at the Academy in Athens—makes their philosophical divergence all the more fascinating. Despite this teacher-student connection, Aristotle developed views that significantly departed from Platonic doctrine, establishing foundations for empirical science that would shape intellectual history in ways distinct from Plato's more idealistic approach.

As Alfred North Whitehead famously observed, "The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato." Yet many of those footnotes were written by Aristotle himself, whose systematic approach to knowledge and emphasis on careful observation of the natural world provided an alternative philosophical framework that has been equally influential.

Their philosophical differences can be symbolized by Raphael's famous depiction in "The School of Athens": Plato pointing upward to the transcendent realm of Forms, Aristotle gesturing outward to the empirical world. This contrast—between Plato's focus on eternal, universal ideals and Aristotle's attention to particular, material realities—runs through nearly every aspect of their philosophical systems.

This comparison will explore their biographical contexts, metaphysical frameworks, approaches to knowledge, ethical theories, political philosophies, and lasting influences. Through understanding both their similarities and differences, we gain insight into two foundational approaches to philosophical inquiry that continue to shape how we think about reality, knowledge, virtue, and society.

Biographical Contexts

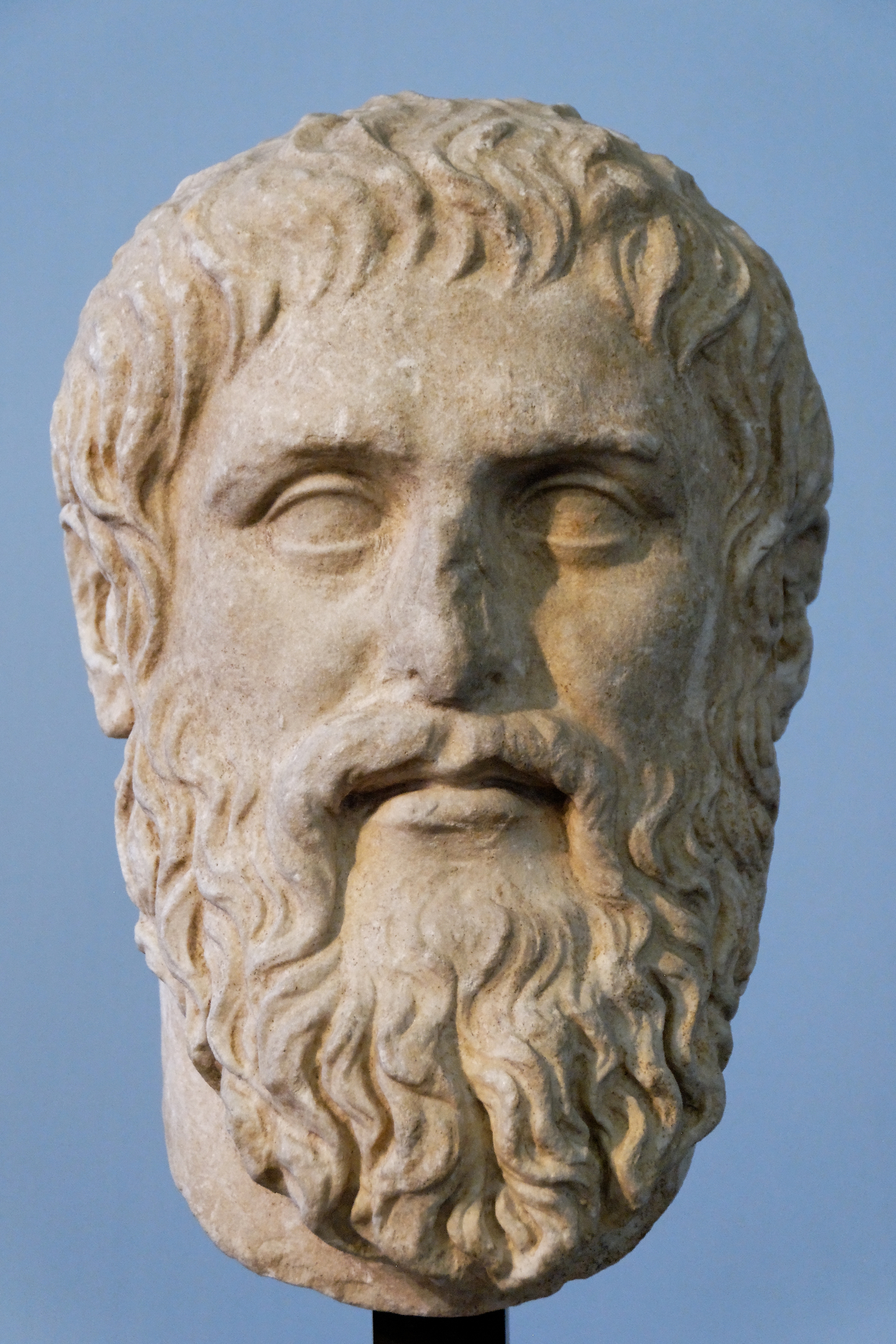

Roman copy of a bust of Plato

Plato

Dates: 428/427 - 348/347 BCE

Background: Born into an aristocratic Athenian family, Plato was influenced by Socrates, whom he met around 407 BCE and whose execution in 399 BCE profoundly shaped his thinking. After Socrates' death, Plato traveled extensively before returning to Athens to found the Academy around 387 BCE, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world.

Historical Context: Plato lived during Athens' transition from the height of its power through the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) to its defeat by Sparta and subsequent political instability. This turbulent period, including the trial and execution of Socrates under the restored democracy, likely influenced Plato's skepticism toward democracy and his search for unchanging truths beyond the political realm.

Major Works: Wrote in dialogue form, with key works including the Republic, Symposium, Phaedo, Phaedrus, Meno, Theaetetus, and Laws.

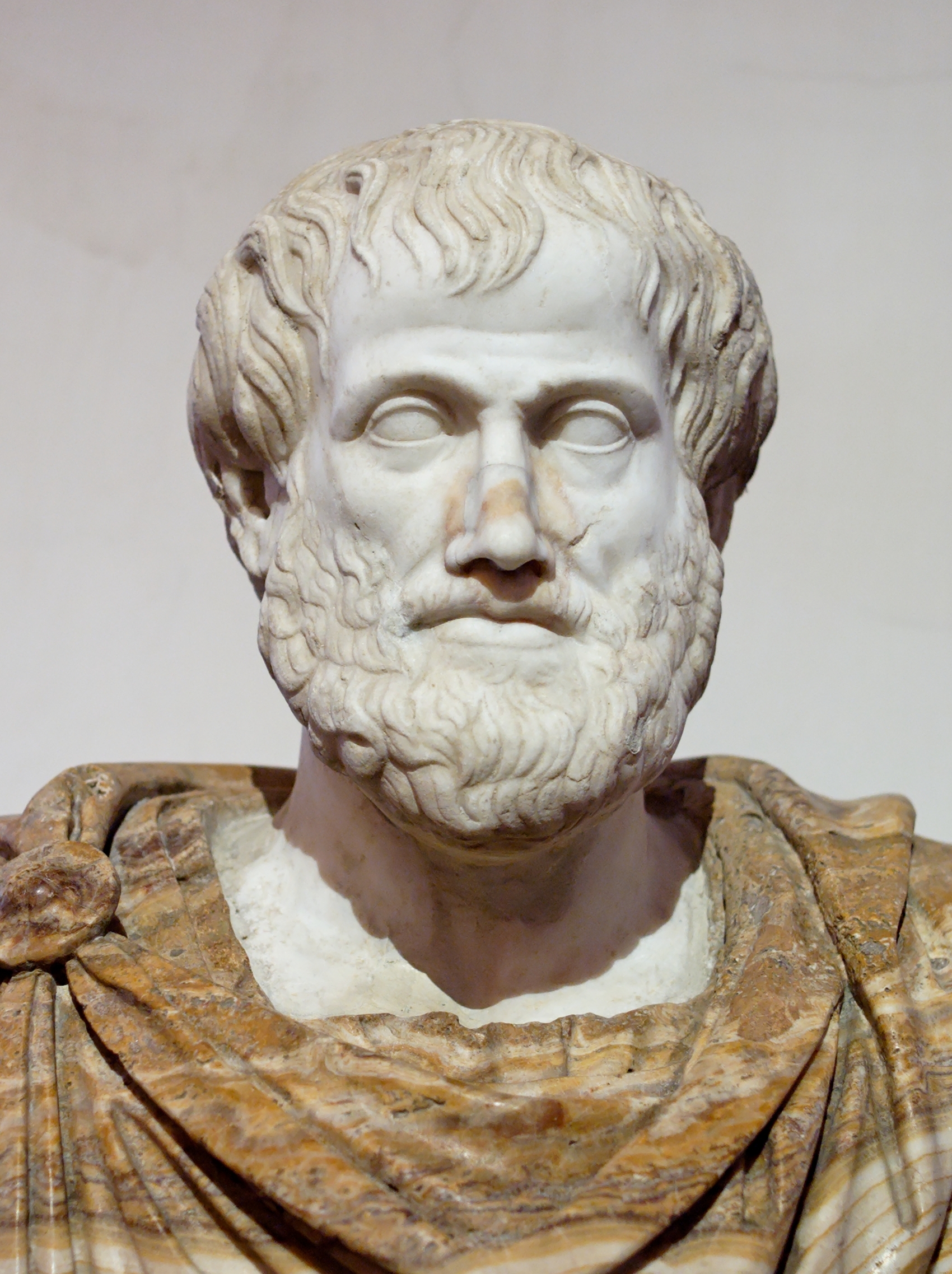

Roman copy of a bust of Aristotle

Aristotle

Dates: 384 - 322 BCE

Background: Born in Stagira in northern Greece, Aristotle's father was a physician to the Macedonian royal court. At age 17, he joined Plato's Academy in Athens, where he remained for nearly 20 years until Plato's death. After leaving the Academy, he tutored Alexander the Great from 343-335 BCE before returning to Athens to found his own school, the Lyceum.

Historical Context: Aristotle witnessed the rise of Macedonian power under Philip II and Alexander the Great, which fundamentally altered the Greek political landscape. His connections to the Macedonian court likely influenced his more empirical and pragmatic approach to philosophy, as well as his extensive research in biology and natural science.

Major Works: Wrote treatises rather than dialogues, covering nearly every field of knowledge. Key works include the Nicomachean Ethics, Politics, Metaphysics, Physics, De Anima (On the Soul), Poetics, and various works on logic collectively known as the Organon.

428/427 BCE

Plato born in Athens into an aristocratic family

c. 407 BCE

Plato meets Socrates and becomes his student

399 BCE

Execution of Socrates, a pivotal event for Plato's philosophy

384 BCE

Aristotle born in Stagira, northern Greece

c. 387 BCE

Plato founds the Academy in Athens

c. 367 BCE

Aristotle joins Plato's Academy at age 17

348/347 BCE

Plato dies in Athens, having completed his final work, the Laws

347 BCE

Aristotle leaves the Academy after Plato's death

343-335 BCE

Aristotle tutors Alexander the Great

335 BCE

Aristotle returns to Athens and founds the Lyceum

323 BCE

Death of Alexander the Great leads to anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens

322 BCE

Aristotle leaves Athens to avoid persecution and dies shortly after in Chalcis

Metaphysics: Reality and Being

Perhaps the most fundamental difference between Plato and Aristotle lies in their metaphysical views—their theories about the nature of reality and existence.

"And now, I said, let me show in a figure how far our nature is enlightened or unenlightened:—Behold! human beings living in an underground den, which has a mouth open towards the light and reaching all along the den; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so that they cannot move, and can only see before them, being prevented by the chains from turning round their heads."

— Plato, Republic, Book VII (The Allegory of the Cave)

"There are many senses in which a thing may be said to 'be', but all that 'is' is related to one central point, one definite kind of thing, and is not said to 'be' by a mere ambiguity."

— Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book Gamma

| Aspect | Plato | Aristotle |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Reality | The Forms (or Ideas): eternal, unchanging, perfect, transcendent universals that exist independent of the physical world. Physical objects are merely imperfect copies of these Forms. | Individual substances: concrete particular things composed of form (universal) and matter (particular). The form exists in the particular things, not separately from them. |

| Metaphysical Dualism | Strong dualism between the intelligible realm of Forms and the sensible realm of physical objects. The relationship between these realms is described through metaphors like participation, imitation, or presence. | Rejects Plato's dualism of separate realms. Form and matter are principles found within individual substances, not separate realms of reality. Form is the organizing principle, matter is the potentiality. |

| Universals | Universals (Forms) exist independently of particulars and are more real than particulars. The Form of Beauty exists whether or not any beautiful things exist. | Universals are real but exist only in particulars. We abstract the universal form from our experience of particulars. There is no Form of Beauty separate from beautiful things. |

| Causation | Emphasized formal and final causes. Things are what they are because they participate in the relevant Forms, and the Form of the Good is the ultimate cause of all things. | Developed a theory of four causes: material (what something is made of), formal (what makes it what it is), efficient (what brought it about), and final (its purpose). All four are necessary for complete explanation. |

| Being and Becoming | Sharp distinction between Being (the unchanging reality of the Forms) and Becoming (the constantly changing physical world). True knowledge concerns Being, not Becoming. | Being is understood in terms of potentiality and actuality. Change is the actualization of what exists potentially. Reality includes both stable forms and the process of development. |

| God/First Principle | The Form of the Good is the highest principle, beyond being itself, the source of all other Forms and of knowledge. Later interpreted as God by Neo-Platonists and Christian thinkers. | The Unmoved Mover (Prime Mover) is pure actuality with no potentiality, eternal, and the ultimate cause of all motion. It is thought thinking itself, the perfect intellect. |

This fundamental metaphysical divergence—Plato's transcendent Forms versus Aristotle's immanent forms—shapes virtually all other aspects of their philosophical systems. Plato's metaphysics leads toward idealism and rationalism, emphasizing the mind's capacity to grasp eternal realities beyond the senses. Aristotle's approach points toward a kind of moderate realism and empiricism, emphasizing careful observation of the natural world combined with rational analysis.

Epistemology: Knowledge and Method

Just as Plato and Aristotle differed in their views on the nature of reality, they also developed contrasting theories of knowledge and methods of inquiry.

"But when the soul investigates by itself, it passes into the realm of what is pure, ever existing, immortal and unchanging, and being akin to this, it always stays with it whenever it is by itself and can do so; it ceases to stray and remains constant as it is in contact with things of the same kind, and its experience is what we call wisdom."

— Plato, Phaedo

"All men by nature desire to know. An indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves... The reason is that this, most of all the senses, makes us know and brings to light many differences between things."

— Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book Alpha

| Aspect | Plato | Aristotle |

|---|---|---|

| Source of Knowledge | Reason and recollection. The soul innately possesses knowledge of the Forms from its pre-embodied state; learning is recollecting what the soul already knows. The senses provide only opinion (doxa), not true knowledge (episteme). | Sensory experience and abstraction. Knowledge begins with perception, from which the mind abstracts universal concepts. "There is nothing in the intellect that was not first in the senses," but reason goes beyond perception to grasp universals. |

| Objects of Knowledge | The Forms. True knowledge concerns what is unchanging and eternal. Knowledge of the physical world is mere opinion, as the physical world is constantly changing. | Particulars and universals. We can have scientific knowledge of both individual substances and the universal forms abstracted from them. Knowledge involves understanding causes. |

| Method | Dialectic. Through question-and-answer dialogue (exemplified by Socrates), one moves from opinion to knowledge by testing definitions and uncovering contradictions. The goal is to ascend to direct intellectual intuition of the Forms. | Empirical observation and logical analysis. Systematic collection of data, categorization, and application of logical reasoning to discover causes and principles. Developed the syllogism as a tool of deductive reasoning. |

| Certainty | True knowledge must be certain, infallible, and unchanging, just like its objects (the Forms). Opinions about the sensible world are always fallible. | Different degrees of certainty are possible in different domains. Mathematics and metaphysics can achieve high certainty, while natural science and ethics have lower degrees of precision. |

| Education | Education involves turning the soul away from the sensible world toward the intelligible realm. In the Republic, the educational curriculum (music, gymnastics, mathematics, dialectic) aims to develop philosopher-kings capable of grasping the Forms. | Education builds on natural curiosity and sensory experience. It involves developing proper habits (for ethical knowledge) and learning the principles of various disciplines through instruction and practice. |

These epistemological differences reflect their metaphysical commitments—Plato's emphasis on transcendent, unchanging Forms leads naturally to rationalism and the theory of recollection, while Aristotle's focus on form-in-matter leads to a more empirically grounded approach. Their different methods of inquiry also influence their writing styles: Plato's philosophical dialogues model the dialectical method, while Aristotle's systematic treatises reflect his analytical approach to organizing knowledge.

Ethics: Virtue and the Good Life

Despite their metaphysical and epistemological differences, Plato and Aristotle share significant common ground in ethics, both emphasizing virtue and the cultivation of character. However, their approaches to ethical questions still reflect their broader philosophical frameworks.

"The just man does not permit the several elements within him to interfere with one another, or any of them to do the work of others—he sets in order his own inner life, and is his own master and his own law, and at peace with himself."

— Plato, Republic, Book IV

"For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them. Men become builders by building and lyre players by playing the lyre; so too we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts."

— Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book II

| Aspect | Plato | Aristotle |

|---|---|---|

| The Highest Good | Knowledge of the Form of the Good, which illuminates all other Forms. This knowledge brings harmony to the soul and allows one to live virtuously. Justice is the proper ordering of the soul's parts, which produces happiness. | Eudaimonia (flourishing or well-being), which is achieved through virtuous activity according to reason. The goal is not just to know what is good but to become good through virtuous action. Happiness requires both virtue and external goods. |

| Theory of Virtue | Identifies four cardinal virtues: wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice. Virtue is knowledge; once one knows what is good, one will act accordingly. Vice results from ignorance of the good. | Distinguishes intellectual virtues (wisdom, understanding, prudence) from moral virtues (courage, temperance, generosity, etc.). Virtue is a habit or disposition to act in the right way, at the right time, toward the right people, for the right reason—the "golden mean" between excess and deficiency. |

| Psychology | The soul has three parts: rational, spirited, and appetitive. Justice occurs when these parts are in proper harmony, with reason ruling, spirit supporting reason, and appetites being controlled. | The soul has rational and non-rational parts. The non-rational includes both the vegetative (controlling nutrition, growth) and the appetitive (desires, emotions). Virtue requires training appetites to follow reason. |

| Moral Development | Emphasizes rational understanding and philosopher-kings as models. People do wrong because they mistake apparent goods for true goods. Proper education and philosophical insight correct these mistakes. | Emphasizes habit formation and practical wisdom. Becoming virtuous requires both proper upbringing to develop good habits and practical wisdom (phronesis) to discern the right action in particular circumstances. |

| Pleasure | Distinguishes between true and false pleasures. Higher pleasures come from knowledge and virtue; lower pleasures from bodily satisfaction. The philosophical life is both virtuous and ultimately most pleasant. | Pleasure is not the goal of life but accompanies successful activity. Different kinds of pleasure correspond to different activities. The highest pleasures come from intellectual activity and virtuous action. |

| Social Dimension | Ethics and politics are inseparable. Justice in the soul mirrors justice in the state. Individual virtue depends partly on living in a just society, which requires philosopher-kings. | Humans are "political animals" by nature, meant to live in communities. Full virtue requires friendship and participation in political life. The virtuous person contributes to the common good. |

Despite these differences, Plato and Aristotle agree on several fundamental ethical points: virtue is central to the good life, reason should guide human action, character development is essential, and ethical flourishing has both individual and social dimensions. Their ethical theories represent two of the most influential virtue ethics approaches in Western philosophy.

Political Philosophy: The Ideal State and Governance

Both Plato and Aristotle devoted significant attention to political philosophy, developing theories of the ideal state, citizenship, and justice that continue to influence political thought today.

"Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophize, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide... cities will have no rest from evils, nor, I think, will the human race."

— Plato, Republic, Book V

"It is evident that the state is a creation of nature, and that man is by nature a political animal... And it is a characteristic of man that he alone has any sense of good and evil, of just and unjust, and the like, and the association of living beings who have this sense makes a family and a state."

— Aristotle, Politics, Book I

| Aspect | Plato | Aristotle |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal State | In the Republic, the ideal state is governed by philosopher-kings who have knowledge of the Form of the Good. Society is divided into three classes: guardians (rulers), auxiliaries (warriors), and producers, mirroring the tripartite soul. Justice is each class performing its proper function. | No single ideal constitution for all situations. The best constitution depends on specific circumstances, but typically involves a mixed system that balances democratic, oligarchic, and monarchical elements. Aims for a large middle class to create stability. |

| View of Democracy | Highly critical of Athenian democracy, which he saw as rule by the ignorant mob. In the Republic, democracy is ranked as the second-worst constitution (above only tyranny), leading to disorder and eventually tyranny. | More nuanced view. Recognizes problems with pure democracy (potential for majority tyranny), but also sees positive elements when combined with other constitutional principles. Critical of both extreme democracy and extreme oligarchy. |

| Foundation of the State | The state arises from human needs and the division of labor. Its true purpose is to create a setting where justice can flourish and philosophers can lead society toward the Good. | The state exists by nature, not merely convention. Humans are naturally political animals who can achieve their full potential only in political communities. The state exists for the sake of the good life, not merely for security or economic advantage. |

| Education | The state should control education to develop citizens' virtues and identify potential guardians. Education includes music, gymnastics, mathematics, and dialectic, designed to turn the soul toward the Forms. | Education should be public and uniform, aimed at developing virtuous citizens who can both rule and be ruled in turn. It should include both practical training and liberal education to develop moral and intellectual virtues. |

| Property | In the ideal state, guardians and auxiliaries hold property in common and live communally, eliminating private interests that could corrupt their judgment. Producers may own private property. | Critical of Plato's communism. Argues for private property with generous use for friends and the community. Private ownership with common use avoids the problems of both pure communism and pure individualism. |

| Family | For guardians in the ideal state, abolishes traditional family in favor of communal arrangements where children are raised collectively and do not know their biological parents, eliminating family loyalty that could override loyalty to the state. | Defends the natural basis of the family as the fundamental social unit. Critical of Plato's community of women and children, arguing it would dilute natural affection and create less unity, not more. |

| Justice | Justice is each person doing the work for which they are naturally suited, without meddling in others' affairs. Social justice mirrors the harmony of the well-ordered soul. | Distinguishes distributive justice (fair distribution of limited goods) from corrective justice (rectifying wrongs). Justice means treating equals equally and unequals unequally in proportion to their relevant differences. |

These political differences reflect their metaphysical and epistemological positions. Plato's ideal state, governed by those with knowledge of the eternal Forms, is more utopian and hierarchical. Aristotle's political theory, based on observation of actual states and recognition of circumstantial variation, is more empirical and pragmatic. Both thinkers, however, see politics as integrally connected to ethics and conceive of the state as existing for the moral development of citizens, not merely for security or economic prosperity.

Legacy and Influence

The contrasting philosophical approaches of Plato and Aristotle have shaped Western thought for over two millennia, with periods where one or the other's influence predominated and many attempts to synthesize their insights.

Classical and Hellenistic Period

Plato's immediate legacy was the Academy, which continued until 529 CE, evolving through several phases including Skeptical and Neo-Platonic periods. Aristotle's Lyceum (the Peripatetic School) was initially more influential in science and empirical studies.

Late Antiquity

Neo-Platonism (Plotinus, Porphyry, Proclus) became dominant, interpreting Plato's Forms hierarchically emanating from the One. Aristotelian logic remained influential even as his metaphysics was often reinterpreted in more Platonic terms.

Islamic Golden Age

Arabic philosophers like Avicenna and Averroes preserved and commented on Aristotle's works, integrating them with Islamic theology. Neo-Platonic ideas also influenced Islamic mysticism (Sufism).

Medieval Period

Early medieval Christianity was heavily influenced by Neo-Platonism through Augustine. The 13th century saw Aristotle's reintroduction to the Latin West, with Thomas Aquinas creating a synthesis of Aristotelian philosophy and Christian theology.

Renaissance

Neo-Platonism experienced a revival through figures like Marsilio Ficino and the Florentine Academy, influencing art, literature, and science. Aristotelian scholasticism remained dominant in universities but was increasingly criticized.

Modern Period

The scientific revolution rejected much of Aristotelian physics while retaining elements of his logical method. Rationalist philosophers (Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz) show Platonic influences, while empiricists (Locke, Berkeley, Hume) have some Aristotelian elements. German Idealism, especially Hegel, represented a kind of Neo-Platonic revival.

Contemporary Philosophy

Analytic philosophy initially emphasized logic and linguistic analysis, with debts to both traditions. Continental philosophy's focus on consciousness and being has Platonic elements. In ethics, virtue ethics represents a revival of both Platonic and Aristotelian moral thought.

Beyond Philosophy

Plato's influence extends to literary theory, psychology (especially Jungian), and political utopianism. Aristotle's influence is seen in biology, ethics, literary criticism, and moderate political theories emphasizing practical wisdom and the middle path.

| Field | Platonic Influence | Aristotelian Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Metaphysics | Idealism, rationalism, theories emphasizing abstract universals, mind-body dualism, transcendence | Moderate realism, empiricism, substance-based ontology, hylomorphism, immanence |

| Epistemology | Rationalism, innate ideas, a priori knowledge, skepticism about sensory knowledge | Moderate empiricism, abstraction from experience, systematic observation, categorization |

| Ethics | Emphasis on knowledge for virtue, otherworldly orientation, unity of virtues | Practical ethics, virtue as habit, golden mean, ethics grounded in human nature |

| Politics | Utopianism, rule by experts, critique of democracy, unified state | Political realism, mixed constitutions, moderation, importance of middle class |

| Theology | Transcendent God, eternal soul, mystical ascent, otherworldly focus | God as first cause or unmoved mover, teleological arguments, systematic theology |

| Science | Mathematical physics, rationalist methodology, theoretical orientation | Biological classification, empirical observation, causal explanation |

Rather than viewing Plato and Aristotle as opposed competitors, we might better see them as representing complementary philosophical approaches that address different aspects of human experience and inquiry. The enduring value of studying both thinkers lies not in choosing one over the other, but in understanding how their different perspectives can enrich our own philosophical inquiry into reality, knowledge, ethics, and society.

Conclusion: Beyond Opposition to Complementarity

While Raphael's "School of Athens" depicts Plato pointing upward and Aristotle gesturing outward, symbolizing their different metaphysical orientations, the painting also shows them walking side by side in conversation. This image captures not just their differences but also their fundamental connection as philosophical interlocutors whose work responds to and builds upon each other.

The traditional narrative has often emphasized the opposition between Platonic idealism and Aristotelian empiricism, between the transcendent and the immanent, between the heavenly and the earthly. While these contrasts are real and significant, focusing exclusively on them risks missing the profound areas of agreement and complementarity between these two philosophical giants.

Both Plato and Aristotle:

- Sought to understand reality through rational inquiry

- Rejected moral relativism in favor of objective ethical standards

- Emphasized virtue and character in their ethical theories

- Saw politics as an extension of ethics, aimed at human flourishing

- Valued wisdom and contemplation as highest human activities

- Believed in a teleological universe with purpose and meaning

Their different approaches—Plato's dramatic dialogues exploring universal ideas through concrete characters and situations versus Aristotle's systematic treatises organizing knowledge into distinct disciplines—reflect complementary paths to philosophical understanding. Plato's myth-making imagination and Aristotle's analytical precision represent different but equally valuable philosophical resources.

Throughout history, the most fruitful philosophical developments have often come not from choosing exclusively between Platonic and Aristotelian approaches but from creative syntheses that incorporate insights from both traditions. From Aquinas's integration of Aristotelian metaphysics with Platonic-Augustinian theology to contemporary virtue ethics drawing on both thinkers, these syntheses recognize that our fullest understanding comes from appreciating both the transcendent and the immanent, both the universal and the particular, both the ideal and the actual.

By studying both Plato and Aristotle, we gain a more complete philosophical perspective that can help us navigate the complex questions of reality, knowledge, ethics, and politics that we continue to face today. Their philosophical conversation, begun over two millennia ago, remains vibrantly alive, inviting us to join in the ongoing quest for wisdom that they so powerfully exemplify.

Further Reading

Primary Sources

- Plato: Republic, Symposium, Phaedo, Theaetetus, Timaeus

- Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics, Politics, Metaphysics, De Anima, Categories

Secondary Sources

- Julia Annas, An Introduction to Plato's Republic

- Jonathan Barnes, Aristotle: A Very Short Introduction

- Terence Irwin, Classical Thought

- G.M.A. Grube, Plato's Thought

- W.K.C. Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy (Volumes on Plato and Aristotle)

- Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics

- Richard Kraut (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Plato

- Jonathan Barnes (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle